Most people expect the war in Iran to end within days or weeks - much like the predictions surrounding Ukraine in February 2022. But a weak regime does not guarantee a short war. It merely means a more unpredictable outcome.

As we wrote in January, the weakening of the Iranian regime has opened a contest for control of the region. Israel, Turkey, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Qatar are all vying for influence - and none of them want the same outcome in this war. Israel and Turkey were already at odds: former Prime Minister Naftali Bennett publicly framed Turkey as a threat on par with Iran. Now Israel is at odds with the Gulf states, whose entire economic model depends on the war ending immediately.

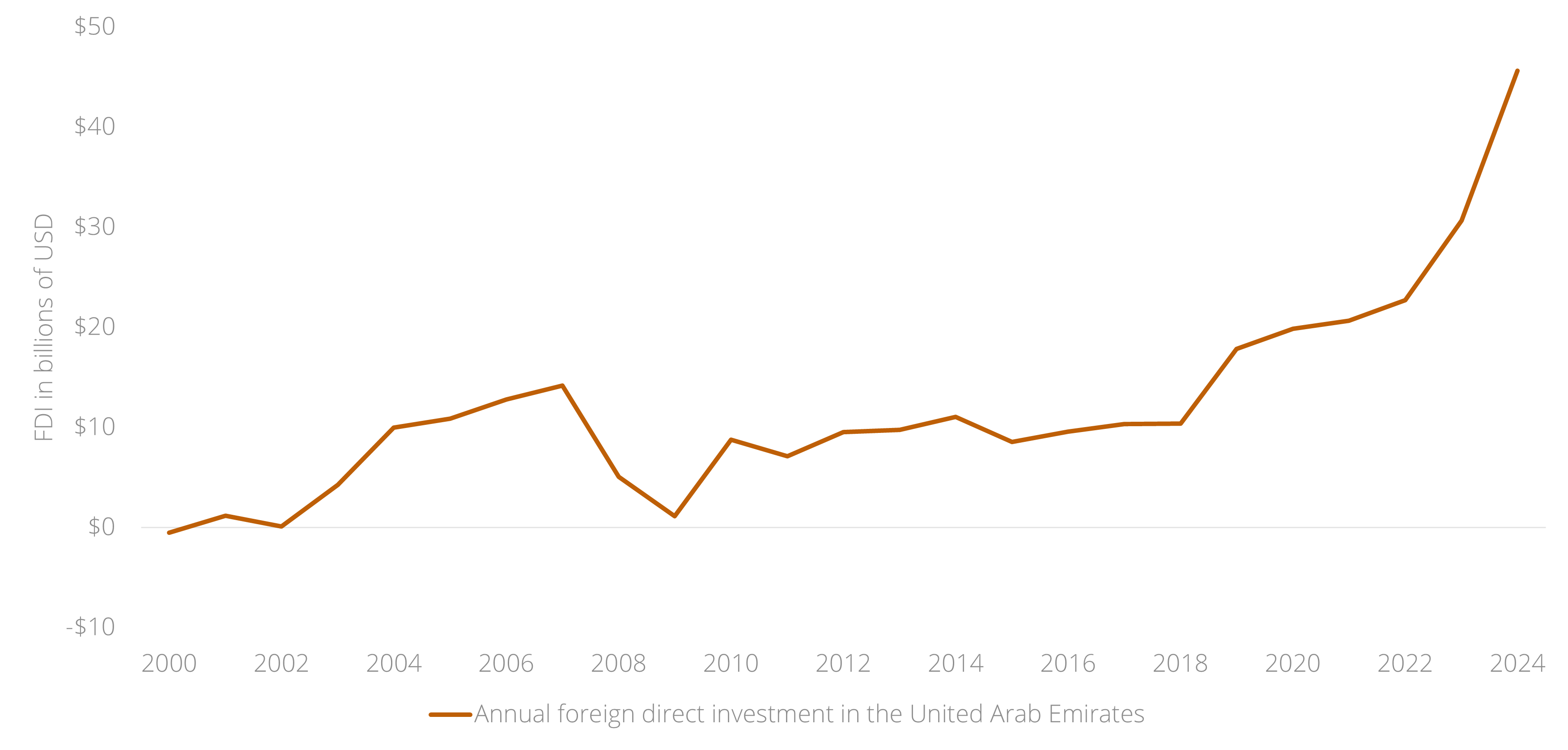

For decades, the Gulf states built their global standing on a single promise: whatever happens in the Middle East, the Gulf remains stable. That promise has now been broken. Missiles have struck Dubai's airport and hotels and killed civilians in Abu Dhabi. Thousands of travelers are stranded across the region - unable to fly home or forced to pay a massive premium to flee via Riyadh. Within days, the Gulf's reputation as a safe haven is already in serious doubt.

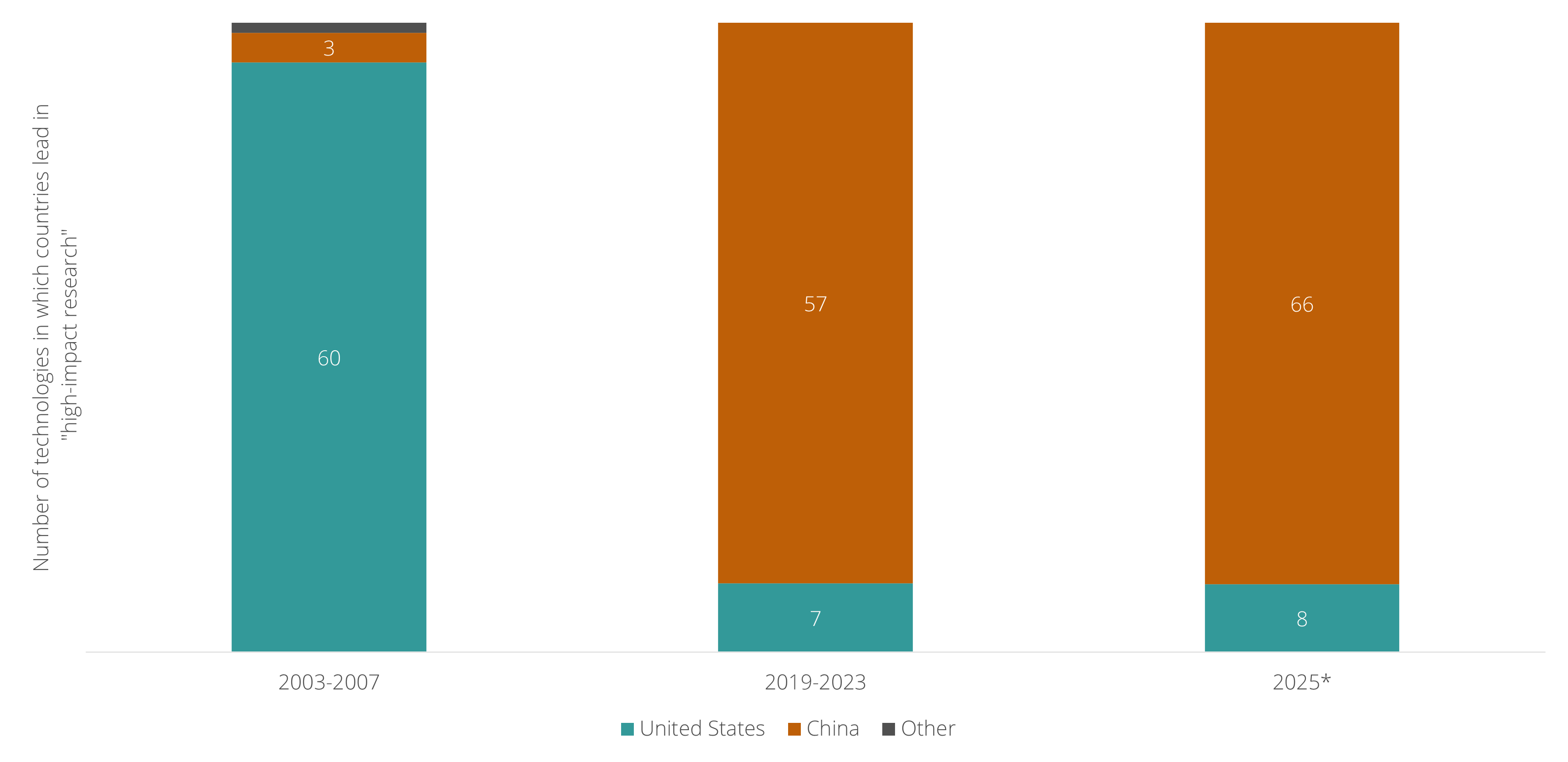

The most common critique of China’s innovation goes like this:

"Sure, China leads in solar panels and batteries – but those were invented elsewhere. And research dominance doesn't mean commercial success.“

It seems like a reasonable critique, but the data doesn't support it.

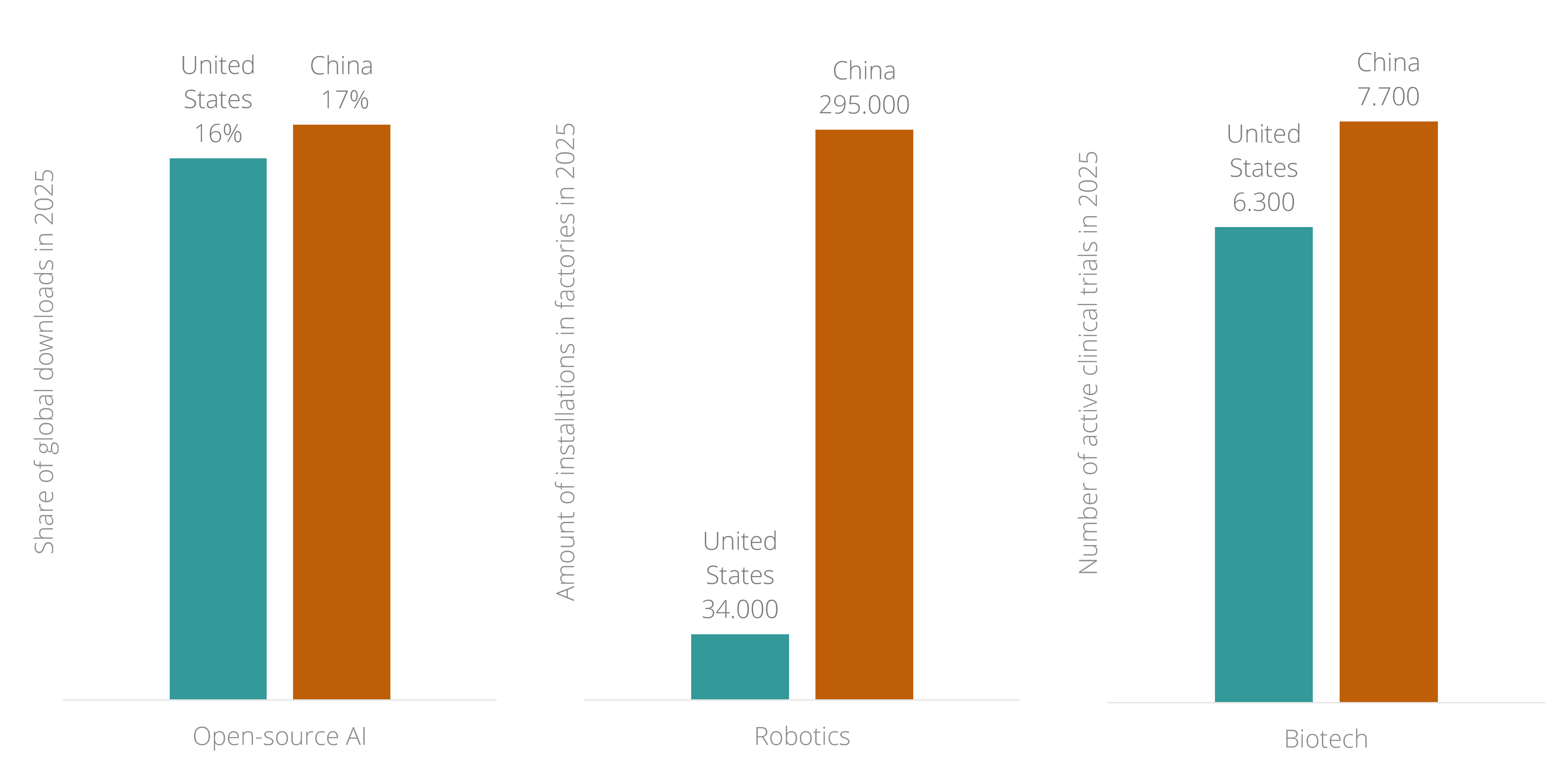

China now leads the US in open-source AI downloads (17% vs 16% globally). It has 8x more industrial robots installed in factories. And it's running more active clinical trials in biotech than the US.

These aren't legacy industries or lab metrics. They're consumer products, factory floors, and drug pipelines.

The question is not whether China is catching up, but whether the West has a good plan for a world where China is leading.

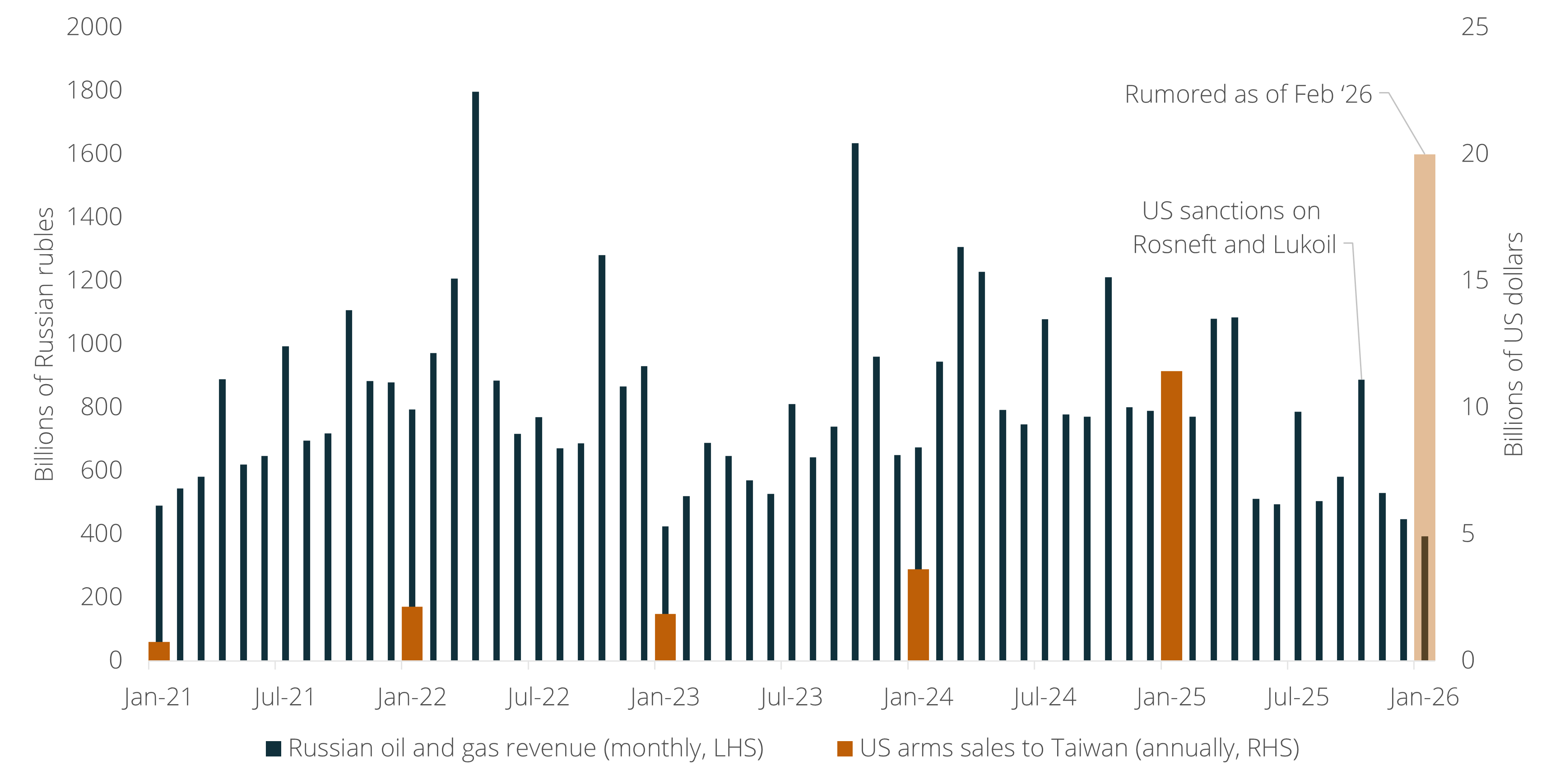

The second Trump presidency has fueled a widespread belief in Europe that Washington has gone soft on China and Russia. But the data tells a different story. US arms sales to Taiwan have accelerated dramatically from a record $11 billion in 2025 to a rumored $20 billion package for 2026. Meanwhile, US sanctions on Russia's two largest oil companies, Rosneft and Lukoil, triggered in October 2025 a collapse in Russian energy revenue to its lowest point in five years, directly threatening the stability of Moscow's war economy.

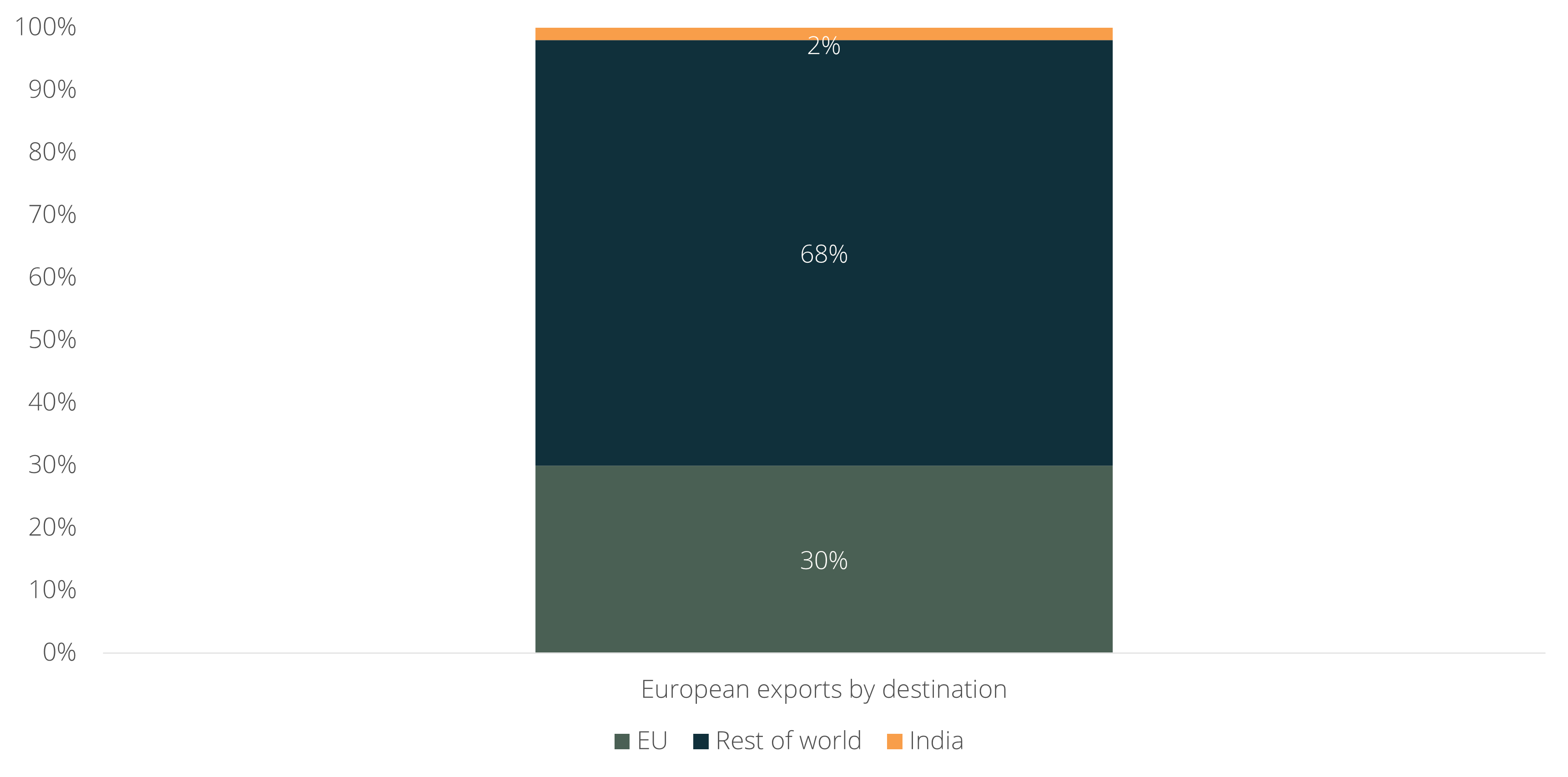

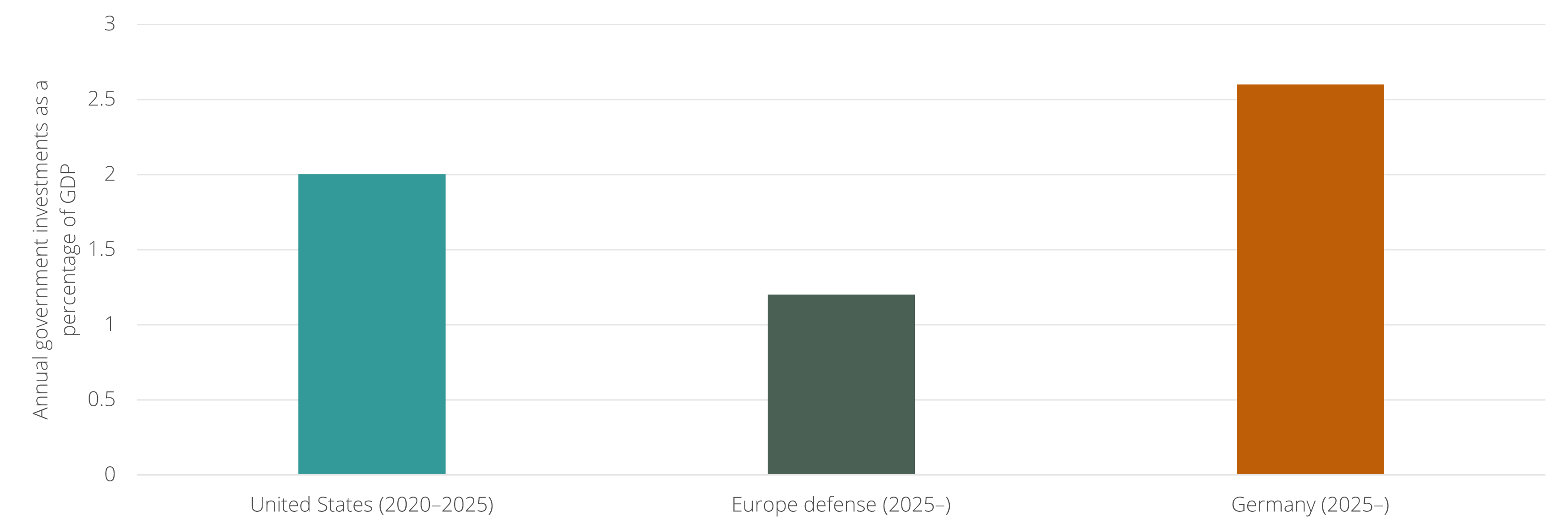

After many years of mainly talk, the EU has grown more ambitious in the past two years, and this trend is accelerating in 2026. Last year, Europe's ambition was driven by an 800 billion euro defense investment plan, in addition to Germany rewriting its constitution to enable bigger government investments. But Europe's two most ambitious projects in 2026 are more structural than these spending programs. First, a trade deal with India - now the world's fourth-largest economy but trading little with Europe - that could open a massive market for European industry. Second, the Industrial Accelerator Act, which will introduce "Buy European" legislation directing EU procurement toward EU suppliers. The biggest challenge remains that some member states oppose projects that lower trade barriers (such as France), whereas others oppose projects that raise them (such as the Netherlands). However, given the current momentum in Europe and the highly uncertain geopolitical situation, the probability that both projects advance is significant. If they do, this could contribute to European stock markets' continued outperformance versus the US, as in 2025.

The extreme volatility in metals markets (in recent days, the price of silver has fallen by nearly 30%) reflects a deep structural problem in Western societies. In recent years, investors have increasingly allocated capital to gold and silver as hedges against the inflation of government-issued currencies – commonly referred to as the “debasement trade.” Behind this investment strategy lies the demographic reality of aging populations. Over the past 50 years, governments have steadily redirected spending toward healthcare and pensions for a growing elderly population, crowding out long-term investment and pushing down economic growth. This has led to record levels of government debt and a greater reliance on inflation as the means of reducing the burden of debt over time. This precarious economy of rising prices, particularly in basic needs such as housing and groceries, has produced a fragile political system defined by the rise of populism.

Because all of this is rooted in demographics, it is likely to persist. Recent policy shifts in the United States and Europe signal an attempt to confront this reality by cutting healthcare and pension commitments, but such measures do not address the underlying problem and are likely to intensify political unrest.

The deeper issue is that governments lack a strategy capable of offsetting the reality of aging populations. One possible exception is China. With a limited tax base to finance its own demographic decline, Beijing has been forced into a more radical response: restructuring its economy toward innovation, including in healthcare itself.

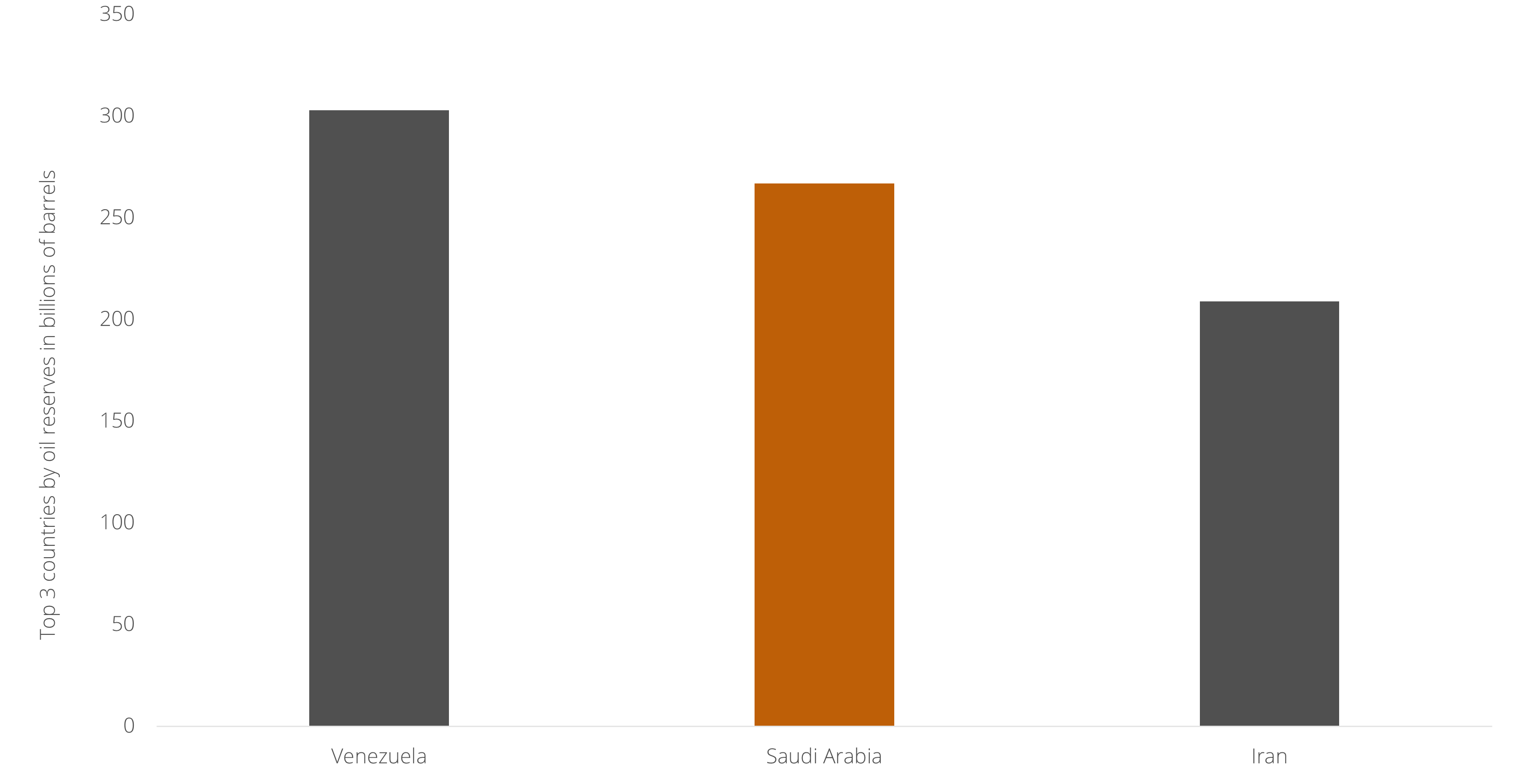

At the start of 2026, just as the United States’ confrontation with other countries threatens global stability, its withdrawal from other regions is also fueling conflict, particularly in the Middle East. The region’s dynamics have shifted fundamentally in the past few years: as the United States retreats, the most powerful country in the region, Iran, has been weakened by its war with Israel following the Hamas attack of October 7, 2023. The result is an open contest for control of the region among five countries: Israel, Turkey, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Qatar. In April 2025, Israel bombed designated sites for three Turkish military bases in Syria, while Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates - until recently longstanding allies - have engaged in proxy conflicts in Yemen, Sudan, Libya, and Somaliland. Looking ahead, it is Saudi Arabia that appears most at risk of triggering a destabilizing scenario, as its future is increasingly threatened by shifting dynamics in the global oil market on which it so heavily depends, driven by rising US production and the prospect of Venezuela, and possibly Iran, regaining access to global oil markets.

As the Western world awaits United States President Trump’s speech in Davos amid an escalating conflict between the US and Europe over the status of Greenland, the prime minister of Canada has returned from China after announcing a “new world order” in which Canada will deepen its relationship with Beijing. This Canadian vision is part of a broader shift across the West: in 2025, Spain joined Hungary in welcoming Chinese producers of batteries and electric vehicles to the European continent, and in the coming weeks the leaders of both the United Kingdom and Germany will visit China in what will likely crystallize into a shared narrative.

As China is increasingly seen as a more reliable partner than the United States by many nations, it is also overtaking the US in technological innovation. In the latest update of the Australian Strategic Policy Institute’s (ASPI) tracker of 74 “critical technologies,” the US leads in just 8, while China leads in 66. Notably, China has recently surpassed the US in the global share of downloads for open-source artificial intelligence models, which are released for free and can run on local cloud providers rather than US- or China-based ones. China’s growing lead in AI is underpinned by its massive advantage in electricity generation: by 2030, its surplus power is projected to be three times larger than the entire world’s electricity demand for data centers. This is also giving rise to entire industries that remain largely unknown in the Western world, such as the “low-altitude economy” (Chinese food-delivery firm Meituan has completed more than 600,000 orders via drones in China).

In 2026, this global shift could shock US financial markets, much as the launch of an AI model by the Chinese firm DeepSeek triggered a panic in January 2025.

What is currently being underestimated is the likelihood that US president Trump, after several high-risk strategic successes (Iran, Venezuela), overplays his hand and makes a mistake similar to Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, which was intended as a quick operation but has turned into a four-year war. If the US were to force Denmark to relinquish control of Greenland, this could become the catalyst for what Europe is currently trying to talk into existence: a new European defense architecture that would effectively replace NATO. If the US were to target Canada, most likely by supporting a secessionist movement in provinces such as Alberta or Quebec, this could spark a nationalist movement to defend Canada, similar to Ukraine’s response to Russian aggression. Besides this, in both scenarios, pressure on the US dollar could intensify, as many Western investors would be incentivized to reduce their dollar holdings. Since 2020, the US dollar has already experienced declining exposure among central banks. If this trend were to accelerate, it could destabilize the US economy through upward pressure on interest rates.

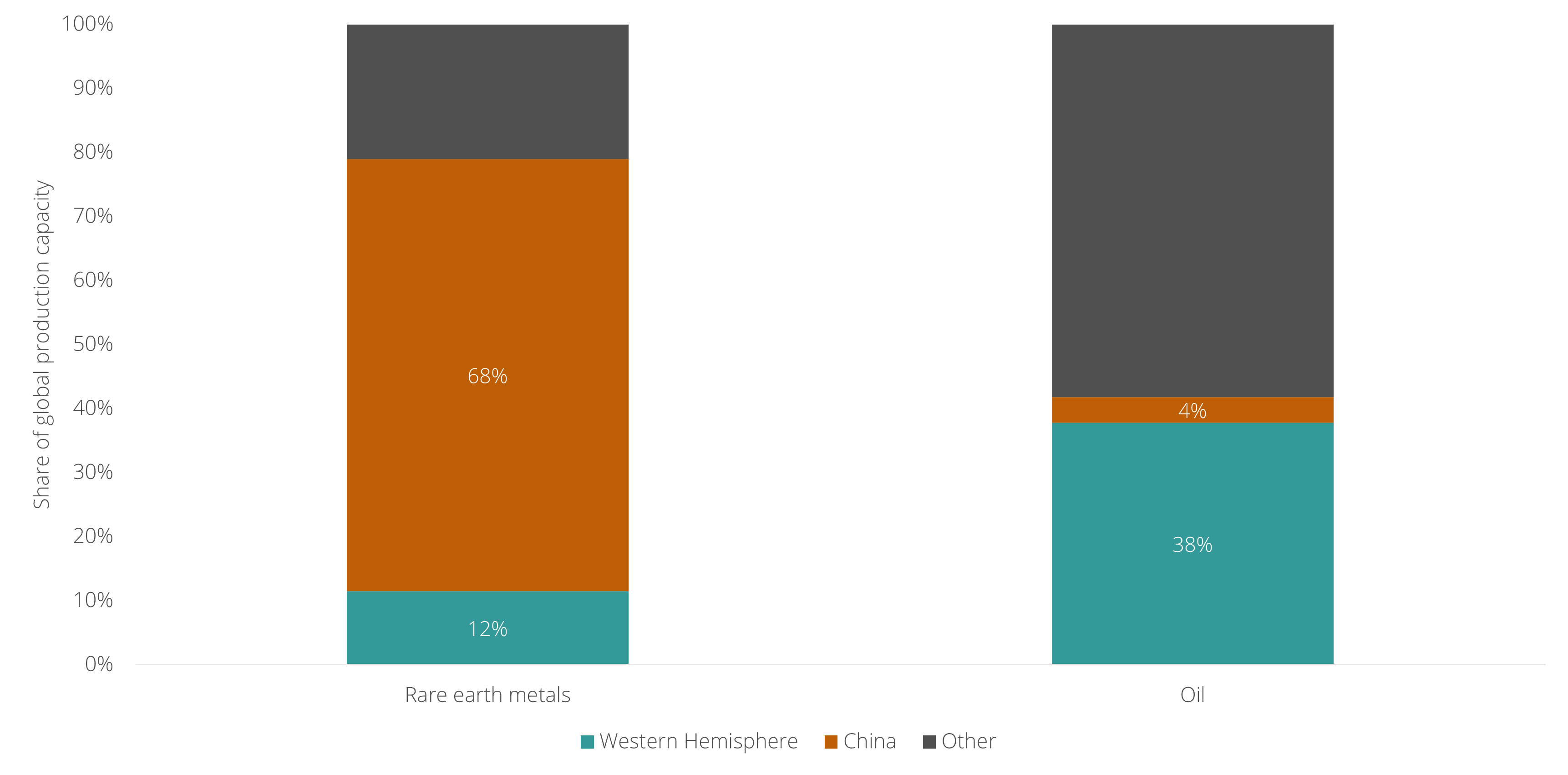

The capture of Venezuelan president Nicolás Maduro by the United States military has shown that Washington is moving decisively to consolidate control over the Western Hemisphere. What remains underappreciated, however, is that by asserting control over these countries, the US would effectively control around 40% of global oil production capacity. This would give the US, for the first time in history, a high degree of influence on global oil prices. Whereas the 1973 oil crisis, driven by Arab producers, once destabilized the US economy, Washington could soon wield comparable leverage over others while keeping energy prices relatively low at home. This strategy thus functions as a structural counterweight to China, which imports roughly 75% of its oil needs but dominates global rare earth metals production capacity. In effect, the US and China are dividing control of the world’s key inputs of economic and military power.

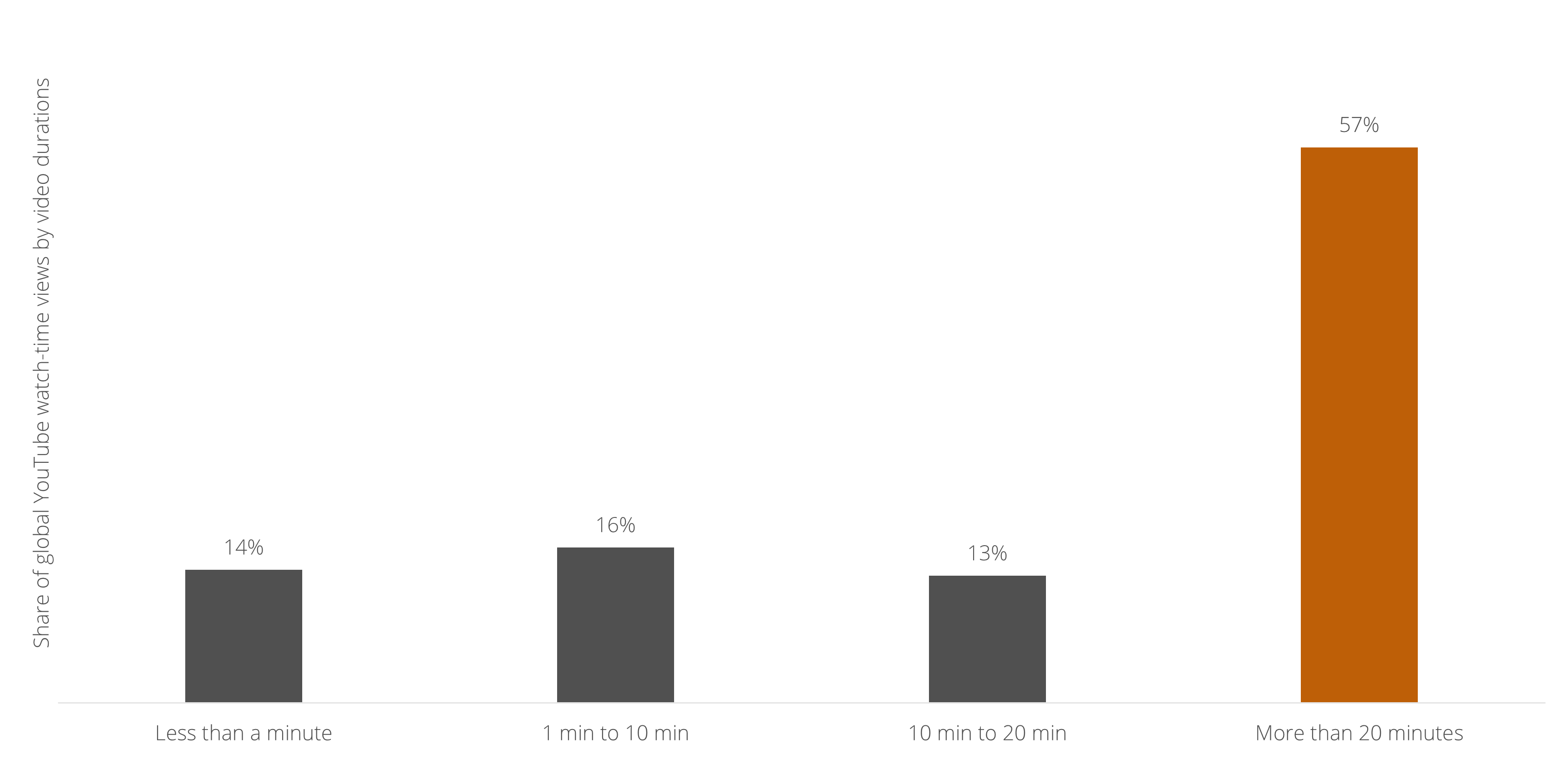

The popularity of media platforms like TikTok, Instagram, and YouTube gave rise to the phenomenon of “doomscrolling,” an activity in which users spend excessive amounts of time ‘mindlessly’ scrolling through short videos, reinforcing the widespread belief that especially young people are addicted to this form of entertainment. Yet the data tells a different story. Although YouTube Shorts of up to three minutes account for around 75% of total views on the platform, more than half of the time spent on YouTube is devoted to videos longer than 20 minutes. At the same time, short-form content is becoming longer: Instagram now allows videos of up to three minutes, and TikTok even permits uploads of up to one hour. The rebirth of long-form video content suggests that young people are not excessively distracted by or addicted to short videos, but are increasingly pushing back against them and seeking longer, more immersive media experiences.

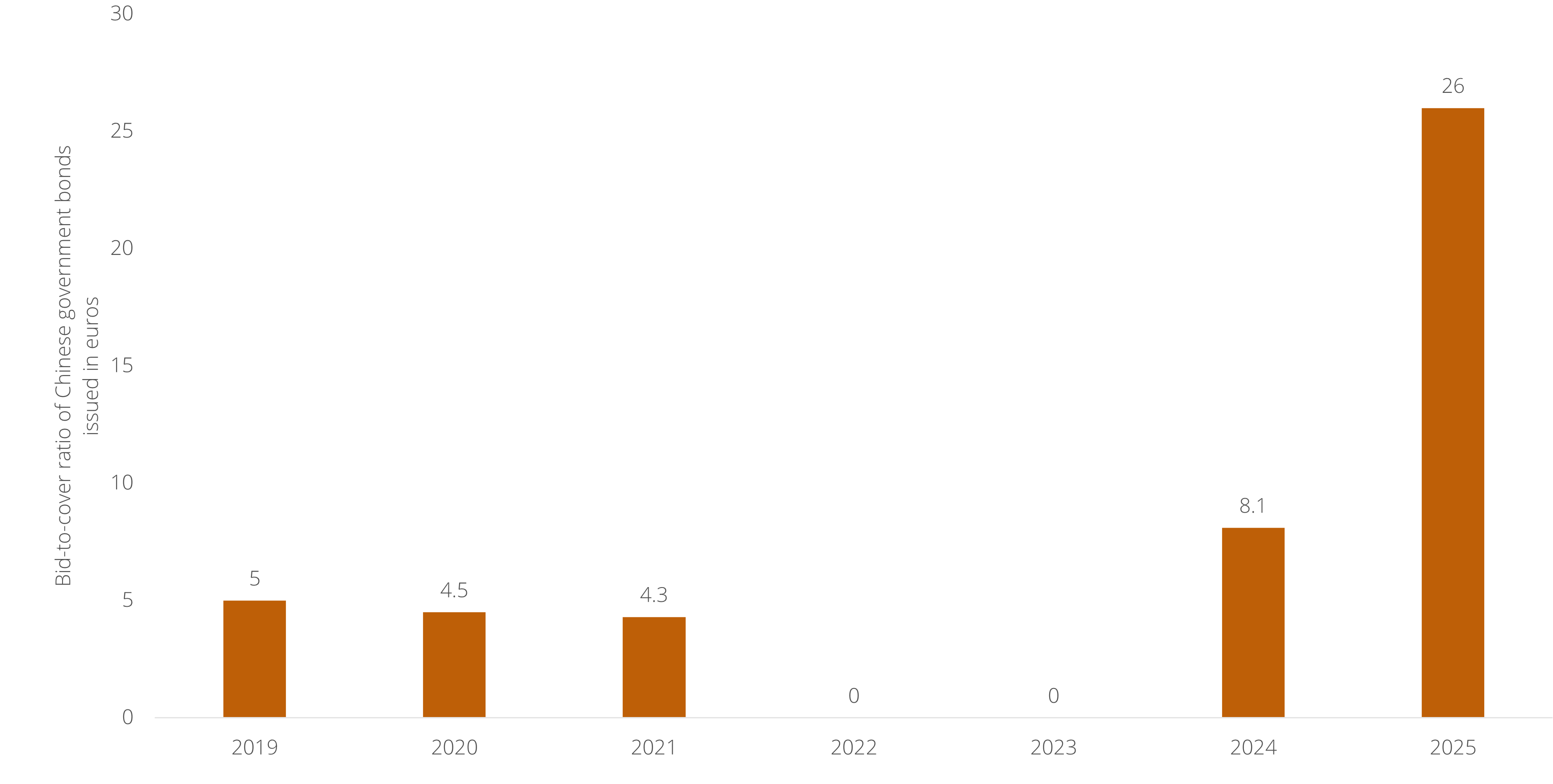

In 2020-21, a wave of unexpected regulations by the Chinese government targeting several sectors, including real estate, private education, and fintech, combined with rising international tensions surrounding the COVID pandemic, led Western financial markets to label China as “uninvestable.” Less than five years later, that consensus has already collapsed. In 2025, Chinese equities rank among the world’s best performing markets. More specifically, China’s power companies are emerging as global leaders underpinning AI investment, with CATL’s batteries becoming the standard even for American data centers. Finally, just weeks ago, China issued government bonds in both US dollars and euros, and demand from Western investors exceeded supply by a factor of 25 to 30, highlighting the growing willingness of Western investors to increase their exposure to Chinese assets.

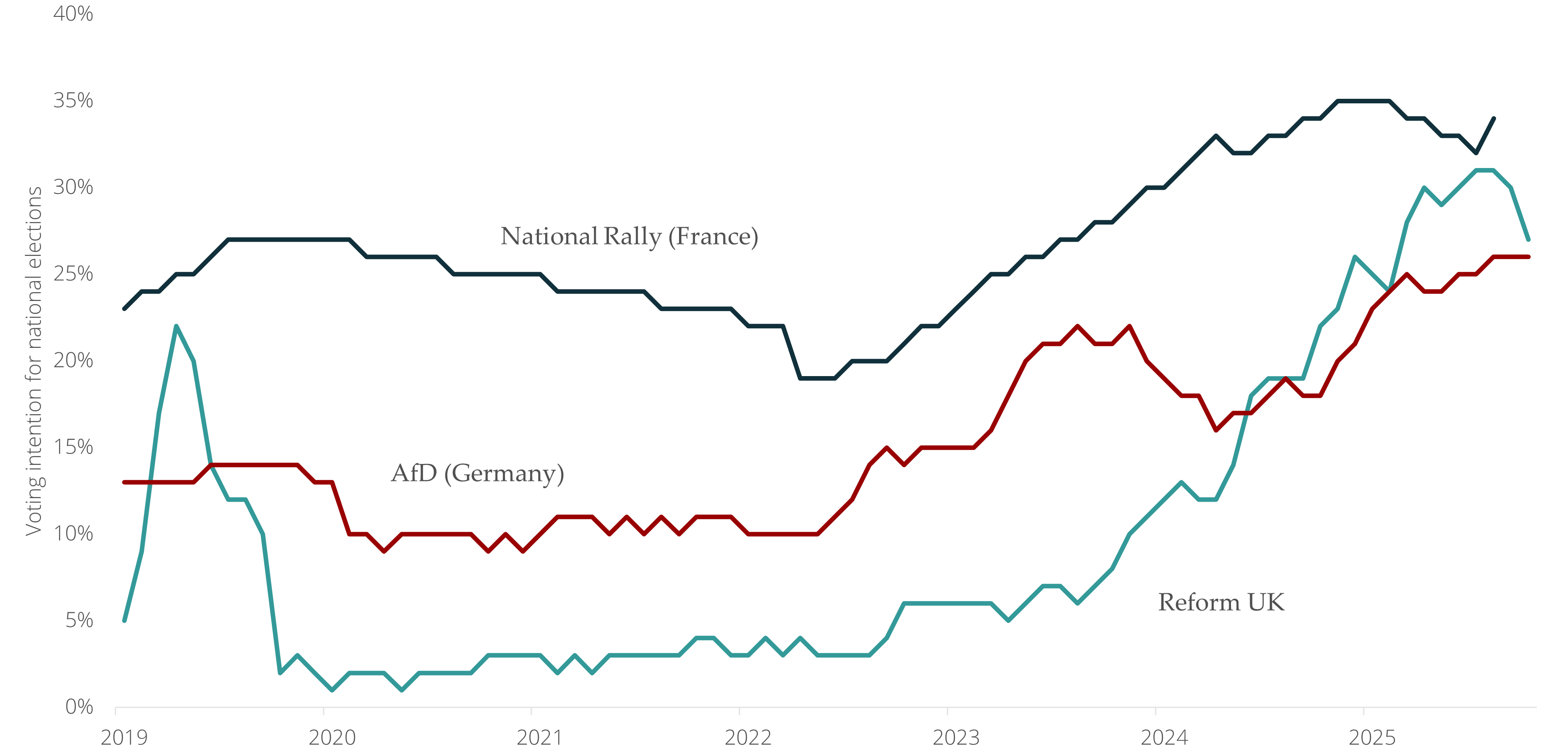

The uproar in Europe over the United States’ new national security strategy, which pledges support for European parties resisting the EU’s supranational power, misses a simple fact: these parties, such as Germany’s AfD and France’s National Rally, are already at the height of their influence, shaping the EU’s agenda from within. Just last month, a united front of right-wing parties in the European Parliament, from "extreme" to moderate, voted to weaken environmental regulations, exempting 80% of companies from the EU’s corporate sustainability reporting rules. More recently, the EU agreed to allow member states to establish asylum processing centers in non-EU countries. In short, even without US meddling, Europe is already drifting away from supranational rulemaking by the EU and toward greater national sovereignty.

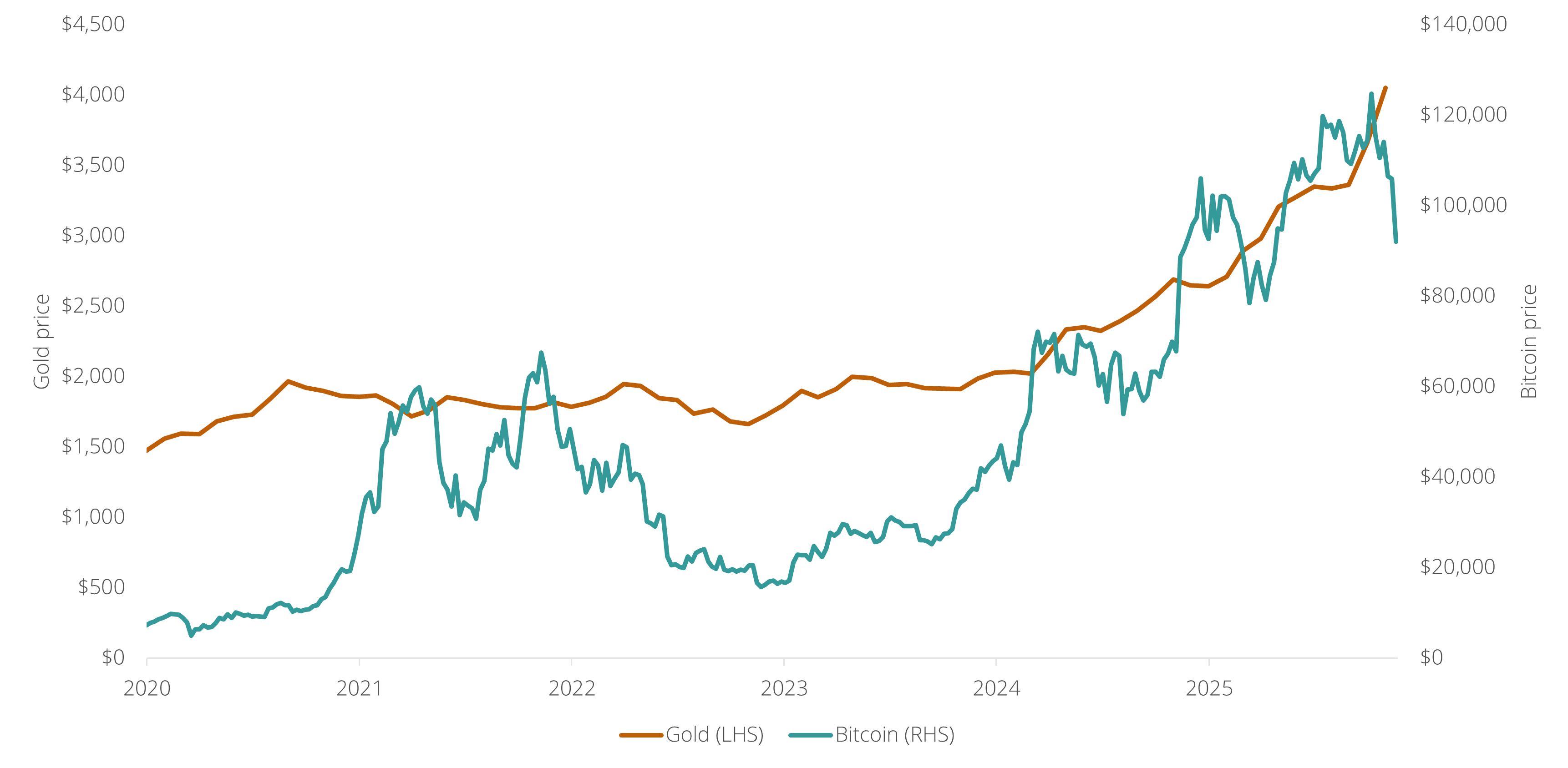

When Bitcoin launched in 2009, it was designed as a form of money that could not be devalued by governments through inflation – unlike dollars and euros that can be created by central banks. Gold has historically served a similar role as a hedge against the eroding value of government-backed currencies, which is why bitcoin enthusiasts have long called it "digital gold". Yet comparing the price development of gold and bitcoin shows a stark contrast: while gold's value is relatively stable, bitcoin has become an extremely volatile asset over the past 17 years, suggesting it does not function as originally intended. A new study indicates that bitcoin also plays a different role. For a growing number of people, cryptocurrency has become a lottery ticket to homeownership. The research shows that among homeowners, crypto ownership rises gradually with wealth, but among renters it is highest among those with the lowest wealth – pointing to a "gambling for redemption" motive: risk-taking as a last resort to become a homeowner.

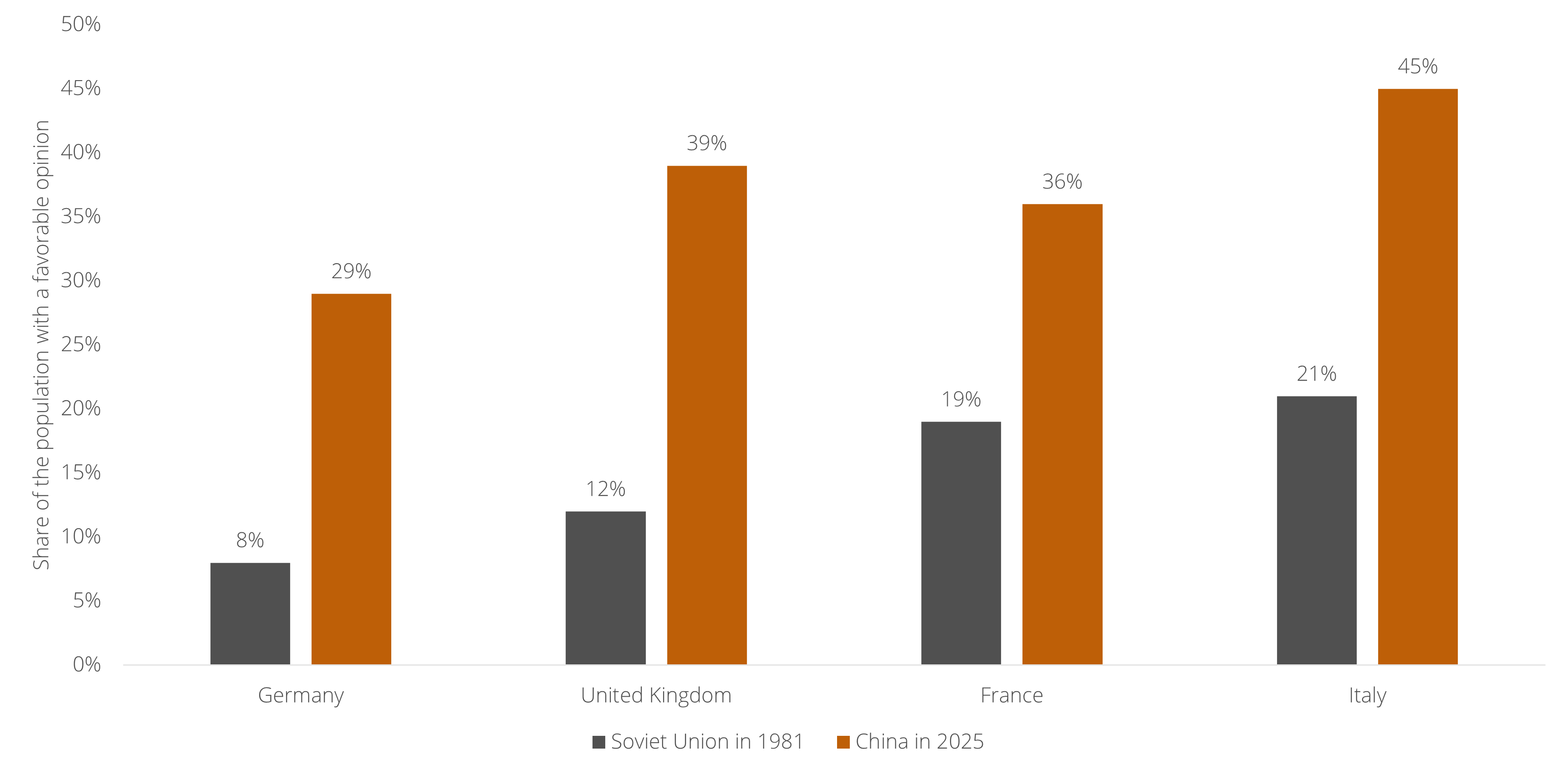

In today’s great-power conflict, many observers cast China as almost a mirror image of the Soviet Union, shaping the narrative that we are living through a “Second Cold War.” Yet one crucial difference between the Soviet Union then and China now is almost never acknowledged: China enjoys a far more favorable image among Western publics than the Soviet Union ever did. Throughout the Cold War, positive views of the USSR rarely exceeded 20% in Europe, whereas in 2025 favorability toward China in some European countries is approaching 50%. A shift is especially pronounced among younger generations, with major social media influencers such as Hasan Piker and IShowSpeed traveling to China in 2025 and telling a positive story about China to their tens of millions of followers – despite accusations of propaganda – focused on China's cutting-edge innovation in robotics and vehicles.

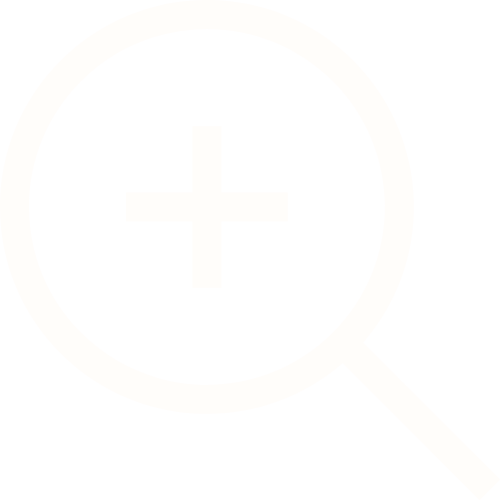

There has been a lot of discussion in recent weeks about the financial markets’ concentration in AI-related companies, with the question whether AI can fulfill its promise at the center of the debate. However, the concentration in AI is only one of five elements in a much bigger and more extreme concentration in the global financial system, reflecting how vulnerable the system has become in the past few years. First, the share of the US stock market as a percentage of the global stock market is at a record high (65%), making many investors, including pension funds, extremely sensitive to a correction in the US stock market. Second, the size of the US stock market relative to the size of the US economy is also at a record high (221%), suggesting that much of the recent growth is based on financial speculation rather than ‘real’ economic value. Third, the share of the top 10 companies in the US stock market is at a record high (41%), indicating that the rest of the economy is growing at a much slower pace (without investments by AI-related companies, the US economy was in recession in 2025). Fourth, US households have never been more invested in the stock market (43% of their wealth), implying that a correction would hit households’ finances relatively hard. Finally, the top 10% of US households (measured by income) own around 90% of the US stock market (a record high) and account for 34% of US consumption (also a record high), suggesting that a market downturn could slow consumer spending and trigger a recession—an unprecedented scenario, as historically it is usually the recession that triggers the market downturn, not the other way around.

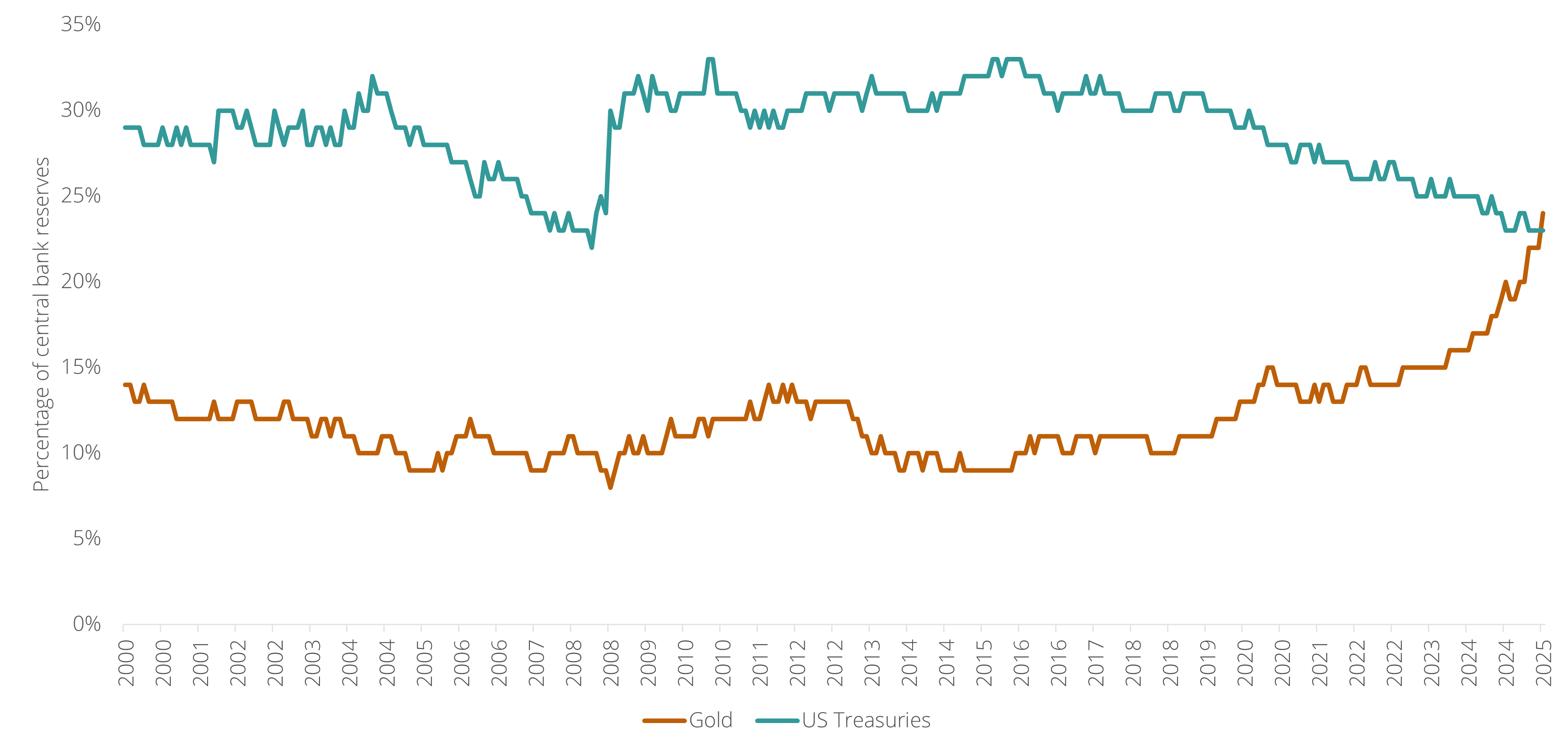

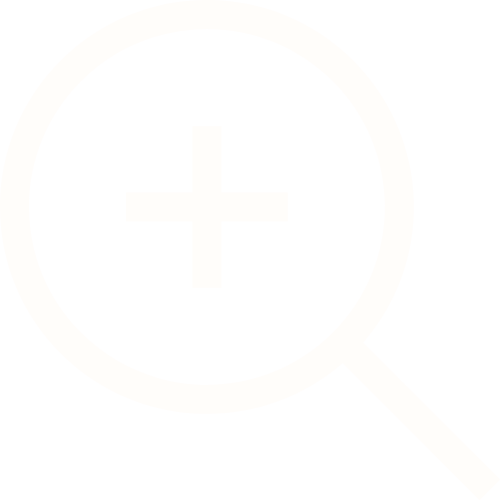

Since this year, central banks hold more gold than US Treasury bonds for the first time since 1996. This trend is driven by two mechanisms. The first is a new type of US foreign policy: as the US seeks to reshape the world order through escalating international conflicts, gold serves as a safer asset compared to US dollars, especially for foreign central banks. Last week, The Financial Times reported that the Chinese central bank may have purchased up to ten times more gold in recent years than official figures suggest. The second mechanism is the fear of a “debasement” of the US dollar, a scenario in which the United States tolerates a higher level of inflation to deflate its large government debt. This fear grows as long as the US president pressures the Federal Reserve to cut interest rates while inflation remains unstable. In the period after 1945, such monetary debasement accounted for at least half of the reduction in government debt in many Western countries, particularly the United States, the United Kingdom, and France.

Amid the focus on Europe’s new defense projects, Germany’s own investment plans have received surprisingly little attention. By removing its budget deficit limit in March of this year, Germany opened the door for government spending that rivals some of history’s largest investment projects. It is set to far exceed the Marshall Plan to rebuild Europe after 1945 and come close to the spending for Germany’s reunification after 1990. It is also expected to surpass US government spending since 2020 (relative to their domestic GDP), which significantly boosted the American stock market over the past five years. Recent reports suggest that nearly 90% of Germany’s investments will flow directly to German companies—a move that could put Berlin at odds with the EU.

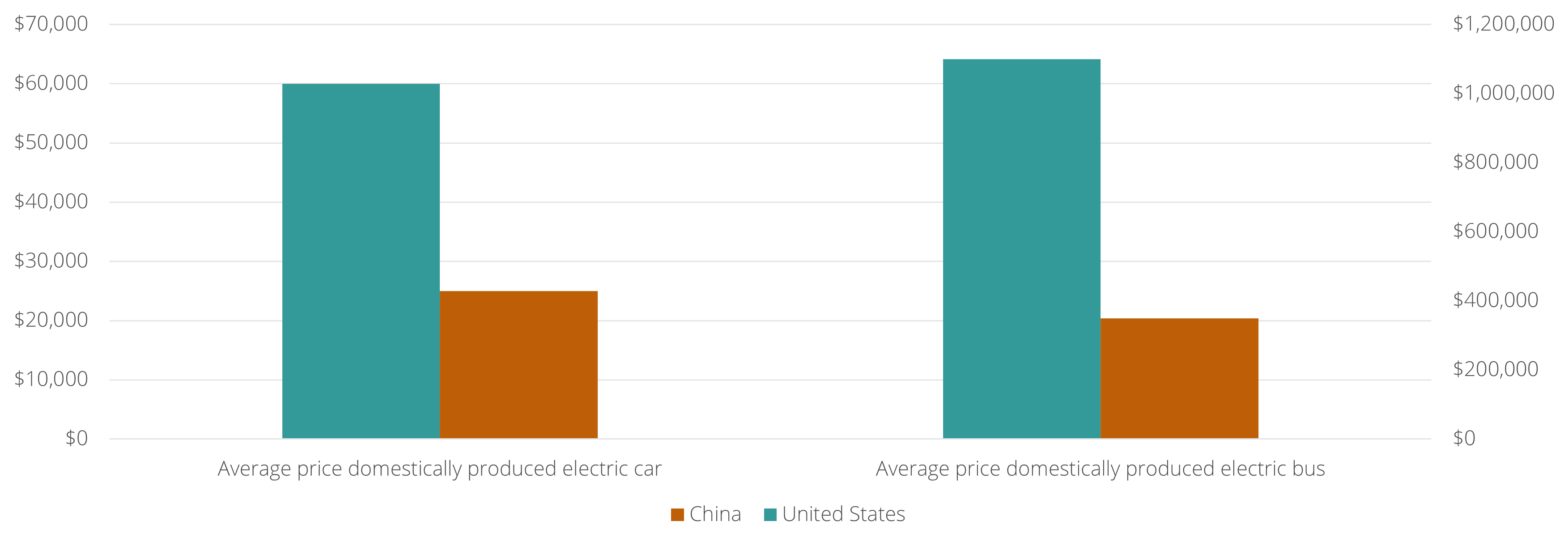

The debate around import tariffs often centers on their short-term impact on inflation. But the long-term impact receives far less attention. As the United States and Europe raise trade barriers against Chinese technology, their populations miss out on large cost advantages. Today, domestically-produced electric cars and -buses from the United States can cost up to three times more than their Chinese equivalents. Given the political unrest over the cost of living across the Western world, it is possible that public opinion will turn against these protectionist policies.

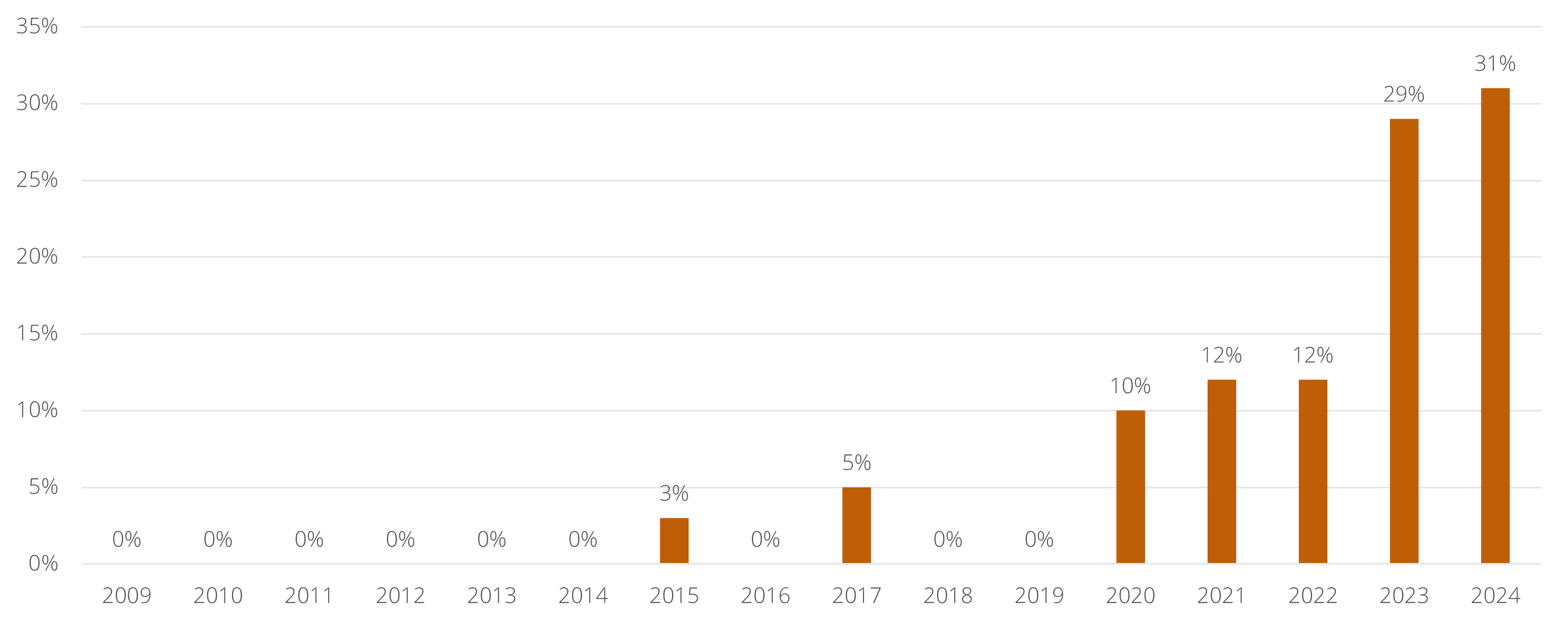

The Western image of China as merely the world’s factory for cheap goods has been dismantled step by step, but the final realization has yet to sink in. In 2020 the pandemic exposed China’s dominance in pharmaceutical ingredients, and in 2025 the West has discovered its control over rare earth metals. In the meantime, China became a global leader in producing high-end batteries and electric vehicles. Still, one shift remains underestimated: China’s ability to push the frontier of innovation. A clear example is biotechnology, where China has emerged as a world leader in developing new medicines — capturing 31% of the global market after starting from zero just a few years ago.

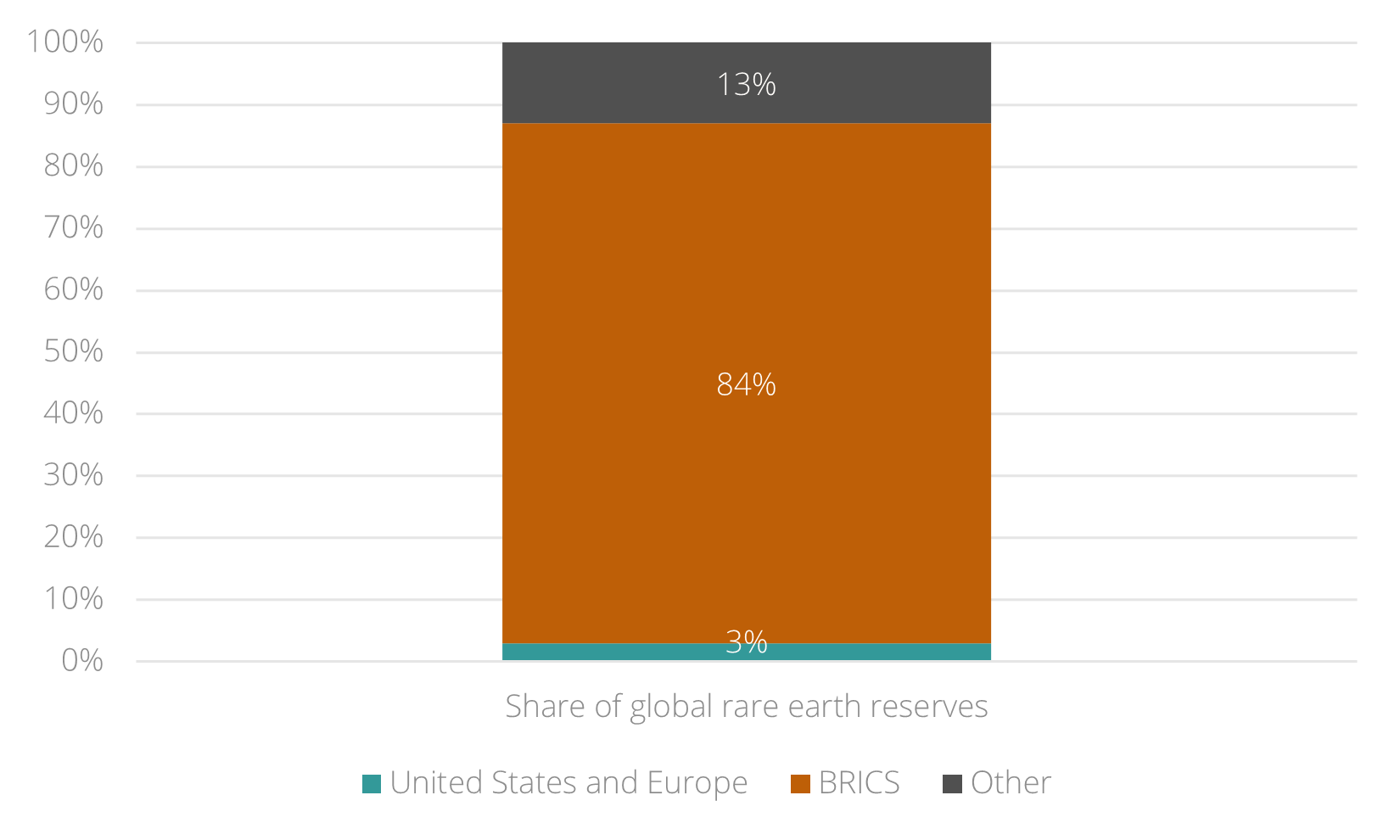

China’s export controls on rare earth metals are part of a broader strategy. Since 2024 the BRICS-countries (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South-Africa) have reportedly been working toward the launch of a new metals trading platform - covering everything from gold and silver to rare earths - that will operate independently of Western exchanges in Chicago and London, as well as Western payment systems like SWIFT. Together, the BRICS control roughly 84% of the world’s rare earth reserves. Much like the Arab OPEC countries during the 1973 oil crisis, the BRICS could use their dominance in critical resources to exert pressure on the United States and Europe.